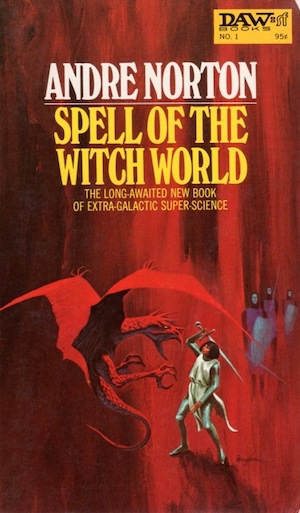

Andre Norton seems to have really liked writing stories set in High Hallack and the Dales of the Witch World. Or maybe her fans really liked her to write them. Three are collected in this volume, two longer works, “Dragon Scale Silver” and “Amber Out of Quayth,” and one much shorter, “Dream Smith.”

They’re all pretty much the same story with some variation. Misfit protagonist learns to wield magic under influence of the long-vanished Old Ones, against a backdrop of the devastating war against the Hounds of Alizon. All three stories feature victims of the war and its aftermath, and all three protagonists have some form of magic.

In “Dragon Scale Silver,” a Witch of Estcarp and her male companion are rescued from shipwreck by villagers along the coast. The Witch sacrifices her life to produce two children, fraternal twins Elys and Elyn. Elys becomes a Wise Woman but is also trained in arms like a boy. Elyn, who has no magic and rejects it totally, becomes a war leader in the Dales. When he sets off to find his martial fortune, Elys conjures with a cup magically fashioned by her mother, to keep track of his life and safety. Eventually and inevitably, the cup warns that Elyn is in danger, and Elys sets off to save him.

She has a companion on the way, a wounded warrior who took refuge in the village. Jervon wants to go back to the war, and insists that she accept his company. This turns out to be a good idea, once she discovers that her brother is under the influence of an evil spell, a curse laid on the family of his fluffy little wife.

Elys saves her brother but receives precious little thanks for it. Elyn rejects magic completely, and his wife actively dislikes everything Elys stands for, from her masculine clothing to her magical heritage. Jervon however is wise and supportive, and they ride off together to fight for the Dales.

“Dream Smith” is the story of a smith who finds metal of the Old Ones and delegates one of his sons to forge it. The son, Collard (one of Norton’s less fortunate naming efforts, though far from the worst), is maimed in the resulting explosion and becomes a recluse, seen and cared for only by the local Wisewoman. He forges bits of the strange metal into wonderful works of art.

In the meantime, the lord’s daughter, who is frail and physically malformed, is dumped in the nearby castle by the lord’s greedy second wife, who wants her out of sight. When the lord dies before the wife can produce a new heir, it’s all too clear that the widow is going to murder the daughter and seize her inheritance.

In order to save the daughter, the Wisewoman and Collard conceive a magical plan. Collard, driven by dreams, builds a miniature hall with an image of the daughter in it, but with a straight and strong body. He finishes it just in time, and the magic takes the daughter away into the dream realm, where she can live side by side with a dream lord.

That lord is not, apparently, Collard. He’s sacrificed his art and his life to save her.

“Amber Out of Quayth” stars gawky young Ysmay, who ruled her family’s keep while the men were off fighting the wars. Now the war is over and her brother has come back with a greedy little wife, and Ysmay is left with nothing but whatever grudging charity the wife deigns to give her. She has only three things to her name: a garden she tends because no one else cares about it, an amber amulet of Gunnora that belonged to her mother and that she’s managed to hide from the grasping Annet, and the ruined remains of an amber mine that collapsed and cannot be reopened.

Then the fair comes to a nearby town, and Ysmay is allowed to accompany the her family. She knows it’s a plot to get her married off, even as poor as she is, but she’s not averse to the concept. Her life is miserable; whoever she’s married to, she’ll become the lady of the hall, and have at least some of her old freedom and responsibility back.

Buy the Book

In the Watchful City

Sure enough, there’s a mysterious amber merchant at the fair, with even more mysterious retainers, and he’s very much interested in her—and in the defunct amber mine, which he claims he can reopen. Hylle marries Ysmay and does indeed open the mine, recovers a few small lumps of amber, and immediately sweeps Ysmay off to his keep in Quayth.

This is a stronghold of the Old Ones, and it’s full of mystery and shadowy magic. Hylle never consummates his marriage with Ysmay—his arts forbid it, he tells her—and he leaves her to the care of one of his repulsive retainers, who is a seeress. Ysmay quickly gets to the heart of the mystery, finds a pair of Old Ones imprisoned in amber, discovers that Hylle needs the amber of her inheritance to strengthen his dark magic, and joins forces with the Old Ones to defeat him. Once she’s done so, she stays in Quayth as its lady, presumably with the male Old One at her side. It’s almost too subtle to see, but she really likes his looks, and the female Old One doesn’t appear to be interested in him, so it’s probably a given that they end up together.

As I read these stories, I kept thinking of the Norton’s own life and experience. The light, almost carefree voice of her earliest works, written in the Thirties, gave way after the Second World War to a completely different tone and emphasis. She became obsessed with apocalyptic disaster, worlds shattered by war, with refugees struggling to survive in the ruins. Often they’re damaged, sometimes physically, always psychologically. They seldom know why they do the things they do; they’re driven by forces beyond their control, compelled to wield weapons and perform functions imposed on them by often incomprehensible powers.

In Witch World especially, systemic misogyny is one of those irresistible forces. Women are each other’s worst enemies, stepmothers are always evil, and girls who are girly are petty and wicked. Sex is icky and deadly and destroys a woman’s powers. Motherhood is almost invariably a death sentence. Character after character is left alone, their mother dead either at their birth or not long after. Jaelithe the Witch is one of the only Norton mothers who not only survives but lives to fight for herself and her family.

And yet, in every Norton novel, no matter how dark, there’s hope. The protagonist finds their way through. Learns to use magic, or lets themself be used to save the world. Discovers who they are, finds their powers, finds a partner to share their future. The war ends, the enemy is defeated.

Whatever the price, the protagonist believes it’s worth it. There’s light ahead—or as one of Norton’s titles has it, there’s No Night Without Stars.

I’ll be rereading that one soon. In the meantime, I’m staying in the Witch World for a little while longer, and moving on from these collected stories to The Warding of Witch World.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Since then she’s written novels and shorter works of historical fiction and historical fantasy and epic fantasy and space opera and contemporary fantasy, many of which have been reborn as ebooks. She has written a primer for writers: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.